Mean Shift

1. Kernel Density Estimation

Kernel density estimation(KDE) is a non-parametric method to estimate the probability density function(pdf). A non-parametric density estimator assumes no pre-specified function form for the pdf. Assume \(X = (x_1, x_2, ... x_n), x_i \in \mathbf{R}^d\) are independent and identically distributed(i.i.d.) random variables with continuous density function \(f\), the kernel density estimator is defined as

\[\begin{equation} \hat{f}(x;H)= \sum_{i=1}^{n} \alpha_i \mathbf{K}(x-x_i, H) \label{eq1} \end{equation}\]where \(\mathbf{K}\) is the kernel, \(H\) is the bandwidth, and \(\alpha_i\) is the weighting coefficient.

1.1 Interpretation

In my understanding, the form of equation \(\eqref{eq1}\) can be interpreted like this:

-

The kernel \(K_i = K(x-x_i, H)\) is the estimated density function for data point \(x_i\)

-

The coefficient \(\alpha_i\) is the weight for data point \(x_i\), usually set as \(1/n\)

-

\(\sum_{i=1}^{n} \alpha_i \mathbf{K}(x-x_i, H)\) is the weighted estimate probability at \(x\)

Given a single data point \(x_i\), when we try to estimate the density function \(K_i\) for \(x_i\), it is nature to assume that:

- the maximum should locate at \(x_i\)

- only the distance to \(x_i\) matters

- the closer to \(x_i\), the bigger the probability

Based on these, a kernel usually satisfies:

- Non-negative, \(K(x) \geq 0\) for all \(x\), probability should be non-negative

- Normalization, \(\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} K(x)d(x) = 1\), results in a pdf

- \(K(0)\) is the maxima

- Non-increasing for distance, \(K(a) \geq K(b)\) if \(\|a \| < \|b\|\)

- Symmetry, \(K(x) = K(-x)\)

The choice of the kernel function is not crucial, the most widely used kernel is the normal kernel

\[\begin{equation} K(x-x_i;H) = \frac{\exp(-\frac{1}{2}(x-x_i)^{T}H^{-1}(x-x_i))}{\sqrt{(2\pi)^d|H|}} \end{equation}\]For more common used kernel functions, please see wiki Kernel (statistics).

1.2 Bandwidth

The bandwidth matrix \(H\) is a symmetric, positive matrix. The choice of bandwidth plays an important role. Selecting an optimal bandwidth is a bias-variance trade-off which is not easy. A large bandwidth has low variance but can leads to oversmoothing. To reduce the complexity, the bandwidth matrix \(H\) is often chosen either as a diagonal matrix \(H = diag[h_1^{2}, ..., h_{d}^{2}]\) with \(d\) bandwidth parameters or a diagonal matrix \(H = h^{2}I_{d}\) with a single bandwidth parameters \(h \neq 0\). This article will consider the later case, combined with the normal kernel, we have

\[\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \hat{f}(x) & = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n K(x-x_i; H) \\ & = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \frac{\exp(-\frac{1}{2}(x-x_i)^{T}H^{-1}(x-x_i))}{\sqrt{(2\pi)^d|H|}} \\ & = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \frac{\exp(-\frac{1}{2h^2}(x-x_i)^{T}(x-x_i))}{h^{d}\sqrt{(2\pi)^{d}}} \end{aligned} \end{equation}\]To make the estimated density function to integrate to one,

\[\begin{equation} \hat{f}(x) = \frac{c_{k, d}}{nh^{d}} \sum_{i=1}^n \exp(-\frac{1}{2} (\frac{x-x_i}{h})^{T} (\frac{x-x_i}{h})) \label{eqnor} \end{equation}\]where \(c_{k, d} > 0\) is the normalization constant.

2. The Mean Shift

The mean shift procedure is an adaptive gradient ascent method to locate the modes of a density function. Given the unknown density function \(f(x)\), the mean shift procedure is a way to locate the modes without estimating the density function. In this case, the modes are the maxima located at the zeros of the gradient \(\bigtriangledown f(x) = 0\). The mean shift procedure is based on the kernel density estimation.

2.1 Equations

In a general way, equation \(\eqref{eqnor}\) can be rewritten as

\[\begin{equation} \hat{f}_{h, k}(x) = \frac{c_{k, d}}{nh^{d}} \sum_{i=1}^n k(\beta {\left\| \frac{x-x_i}{h} \right\|}^{2}) \end{equation}\]where \(\beta < 0\). In the normal kernel case, \(\beta = -\frac{1}{2}\). In this way, the density gradient estimator becomes

\[\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \hat{\bigtriangledown}f_{h, k}(x) & = \frac{2 \beta c_{k,d}}{nh^{d+2}} \sum_{i=1}^n (x-x_i)k^{'} \\ & = \frac{2 \beta c_{k,d}}{nh^{d+2}} \left( \sum_{i=1}^n x k^{'} - \sum_{i=1}^n x_i k^{'} \right) \\ & = \frac{-2 \beta c_{k,d}}{nh^{d+2}} \left( \sum_{i=1}^n k^{'} \right) \left( \frac{\sum_{i=1}^n x_i k^{'}}{ \sum_{i=1}^n k^{'}} - x \right) \end{aligned} \end{equation}\]where

\[\begin{equation} k^{'} = k^{'}( \beta {\left\| \frac{ x-x_i}{h} \right\| }^2) = \partial \left( k( \beta {\left\| \frac{ x-x_i}{h} \right\| }^2) \right) / \partial \left( \beta {\left\| \frac{ x-x_i}{h} \right\| }^2 \right) \end{equation}\]After assigning

\[\begin{equation} g(x) = -\text{sgn}(\beta)k^{'}(x) = k^{'}(x) \end{equation}\]and

\[\begin{equation} y_i = \beta {\left\| \frac{ x-x_i}{h} \right\| }^2 \end{equation}\]we have

\[\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \hat{\bigtriangledown}f_{h, k}(x) & = \frac{-2 \beta c_{k,d}}{nh^{d+2}} \left[ \sum_{i=1}^n g(y_i) \right] \left[ \frac{\sum_{i=1}^n x_i g(y_i)}{\sum_{i=1}^n g(y_i)} - x \right] \\ & = \frac{c}{nh^{d+2}} \left[ \sum_{i=1}^n g(y_i) \right] m(x) \\ \end{aligned} \label{gradient} \end{equation}\]where \(c > 0\) is the positive constant, and

\[\begin{equation} m(x) = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^n x_i g(y_i)}{\sum_{i=1}^n g(y_i)} - x \label{meanshift1} \end{equation}\]is the mean shift, i.e., the difference between the weighted mean and \(x\) the center of the kernel. Therefore, we have

\[\begin{equation} m(x) = \frac{nh^{d+2}}{c} \frac{\hat{\bigtriangledown}f_{h, k}(x)}{\sum_{i=1}^n g(y_i)} \label{meanshift2} \end{equation}\]2.2 The Mean Shift Procedure

The mean shift procedure aims to find the maxima location of \(\hat{f}_{h,k}(x)\). According to equation \(\eqref{meanshift2}\), since \(\frac{nh^{d+2}}{c} > 0\) and \(g(y_i) > 0\) for all \(i\), we have

\[\begin{equation} \hat{\bigtriangledown}f_{h, k}(x) = 0 \iff m(x) = 0 \end{equation}\]Referring to equation \(\eqref{meanshift1}\), we define the weighted mean as \(w(x)\), using \(g\) for weights

\[\begin{equation} w(x) = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^n x_i g(y_i)}{\sum_{i=1}^n g(y_i)} \label{weightedmean} \end{equation}\]Therefore,

\[\begin{equation} m(x) = w(x) - x \end{equation}\]The mean shift procedure as follows:

-

for each instance \(x_i\), at step \(t \geq 0\):

1.1. computes weighted mean \(w(x_t)\) according to equation \(\eqref{weightedmean}\)

1.2 assign \(x_{t+1} = x_t + m(x_t) = w(x_t)\)

-

repeat the above step until converge or reach the max_iter

With the mean shift procedure, we can get the centroid for each data point \(x_i\), and the data points share the same centroid will be labeled as the same cluster. Therefore, mean shift can be applied as clustering.

2.3 Adaptive Gradient Ascent

In my understanding, we can explain the adaptive gradient ascent in this way. According to equation \(\eqref{meanshift2}\), we have

\[\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} m(x) & = \frac{nh^{d+2}}{c \sum_{i=1}^n g(y_i)} \hat{\bigtriangledown f_{h, k}}(x) \\ & = \gamma_{t} \hat{\bigtriangledown}f_{h, k}(x) \\ \end{aligned} \end{equation}\]where

\[\begin{equation} \gamma_t = \frac{nh^{d+2}}{c \sum_{i=1}^n g(y_i)} \end{equation}\]And

\[\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} x_{t+1} & = x_t + m(x_t) \\ & = x_t + \gamma_{t} \hat{\bigtriangledown}f_{h, k}(x) \\ \end{aligned} \end{equation}\]During the process of \(x_t\) approaching to the optimal value \(x^*\), \(f_{h, k}(x)\) becoming bigger, that is, \(\sum_{i=1}^n k(y_i)\) becoming bigger. After applying the normal kernel to \(k\), it is easy to see

\[\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} g(y_i) & = k^{'}(y_i) = \partial k(y_i) / \partial y_i \\ & = \partial \exp(y_i) / y_i = \exp(y_i) \\ & = k(y_i) \end{aligned} \end{equation}\]Therefore, the bigger \(f_{h, k}(x)\), the bigger \(\sum_{i=1}^n g(y_i) = \sum_{i=1}^n k(y_i)\) will be, the smaller \(\gamma_t\). In this case, if \(\gamma_t\) is small enough, the mean shift procedure is an adaptive gradient ascent.

3. A Numpy Python Implementation For Gaussian Mean Shift Clustering

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.datasets import make_blobs

# 1. import data

X, y = make_blobs(n_samples=500, centers=3, n_features=2, random_state=42)

# 2. find centroids

# update centroid using gaussian kernel

# $$g_i = np.exp(-\frac{1}{h^2}(x_t-x_i)^T(x_t-x_i))$$

# $$G = (g_1, ..., g_n)^T$$, h = bandwidth

def update_weighted_mean(X, x_weighted, bandwidth):

diff = x_weighted - X

diff_square = diff*diff

diff_square_sum = np.sum(diff_square, axis=1)

G = np.exp(-diff_square_sum/(2*np.square(bandwidth)))

numerator = X.T.dot(G)

denominator = np.sum(G)

return numerator/denominator

# check if centroid already exist, if exist, return the cluster label

def has_mean(new_mean, means, tol):

for idx, mean in enumerate(means):

if np.allclose(new_mean, mean, atol=tol):

return idx

# 3. the meanshift function

def meanshift(X, bandwidth, max_iter, tol, need_track, track_point_idx):

it = 0

means = None

labels = []

means_track = []

for idx, x in enumerate(X):

x_weighted = x

while it < max_iter:

x_weighted_new = update_weighted_mean(X, x_weighted, bandwidth)

# stop iteration if converged

if np.allclose(x_weighted, x_weighted_new):

break

else:

x_weighted = x_weighted_new

# only track the particular data point

if need_track and idx == track_point_idx:

means_track.append(x_weighted)

it += 1

if it == max_iter:

print('case', idx, 'did not converged')

if idx == 0:

means = np.array([x_weighted])

label = idx

else:

mean_idx = has_mean(x_weighted, means, tol)

if mean_idx is None:

means = np.vstack((means, x_weighted))

label += 1

else:

label = mean_idx

labels.append(label)

return means, np.array(labels), np.array(means_track)

# 4. get results

# In this article, we use sklearn to estimate bandwidth

from sklearn.cluster import estimate_bandwidth

bandwidth = estimate_bandwidth(X)

# In this case, the weighted means converage slowly, so we set max_iter=10000

means, labels, means_track = meanshift(X, bandwidth, 10000, 1e-03, True, 0)

print(means.shape, means_track.shape)

# 5. show results with pyplot and compare with sklearn MeanShift

# 5.1 get sklearn MeanShift results

from sklearn.cluster import MeanShift

sk_ms = MeanShift().fit(X)

def plot_scatter(ax, X, labels, centroids, title):

ax.scatter(X[:, 0], X[:, 1], c=labels, cmap='cividis')

for centroid in centroids:

ax.scatter(centroid[0], centroid[1], c='red')

ax.set_title(title)

# plot the centroid moving track

def plot_track(ax, X_sub, means_track):

start_point = X_sub[0]

end_point= means_track[-1]

dx = end_point[0] - start_point[0]

dy = end_point[1] - start_point[1]

ax.arrow(start_point[0], start_point[1], dx, dy,

alpha=0.5, head_width=0.5, width=0.1, color='red', zorder=10)

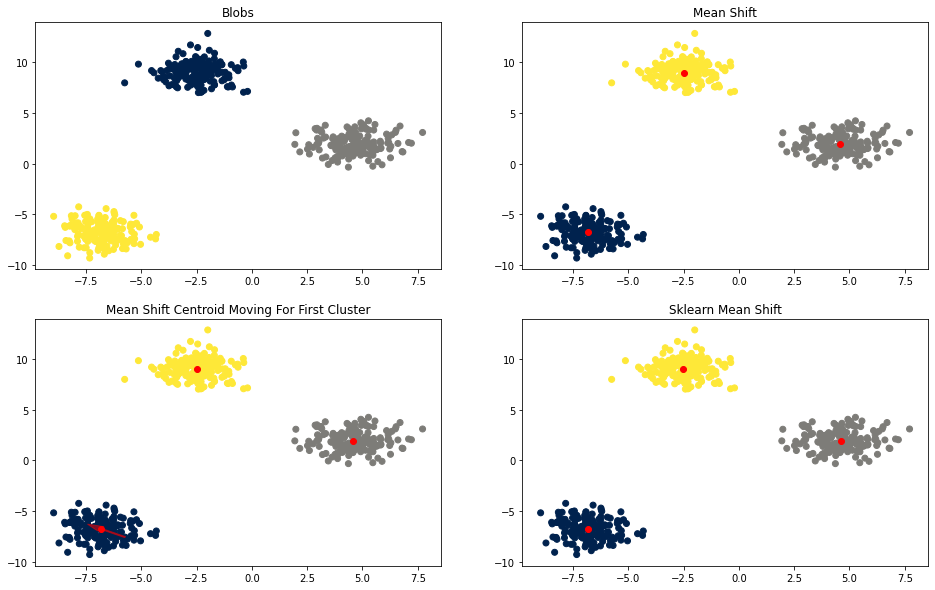

fig, axes = plt.subplots(2, 2, figsize=(16, 10))

plot_scatter(axes[0, 0], X, y, [], 'Blobs')

plot_scatter(axes[0, 1], X, labels, means, 'Mean Shift')

plot_scatter(axes[1, 0], X, labels, means, 'Mean Shift Centroid Moving For First Cluster')

plot_scatter(axes[1, 1], X, sk_ms.labels_, sk_ms.cluster_centers_, 'Sklearn Mean Shift')

plot_track(axes[1, 0], X[labels==0], means_track)

4. References

-

Dorin Comaniciu, Peter Meer(2002). “Mean Shift: A Robust Approach toward Feature Space Analysis”.

-

José E. Chacón, Tarn Duong(2018). “Multivariate Kernel Smoothing and Its Applications”.

-

M. Herbin, N. Bonnet, and P. Vautrot(1996). “A Clustering Method based on the Estimation of the Probability Density Function and on the Skeleton by Influence Zones. Application to Image Processing”.